Engineering Speed Part 1: Start With Clear Problems

Master the art of defining problems well to create a tremendous impact.

This will be part one of a two-part series on two areas that all engineers can level up in: articulating clear problems and making technical decisions.Our Designs Got Stuck in Review

I stepped out of the meeting with two engineering leads on a cross-functional project I was the technical lead on. Over several days of debates on an engineering design, it wasn’t clear to me at first, but we were totally stuck. One engineer was optimizing for governance and control, while the other was optimizing for flexibility. When I asked why, they had two different starting assumptions (one was trying to address systemic risks, which engineering leadership shared was important, and the other was trying to address flexibility, which product stressed was important). At that moment, it was clear to me that I hadn’t created enough clarity on the problems we needed to solve. This manifested later in constructive feedback I received from both engineers, and gave me a moment to reflect on the importance of:

Clear problems and opportunities

Resolute technical decisions that guide virtual teams.

Let’s step a bit into clear problems and opportunities.

Why Clear Problems Are So Important

As a cross-functional T-shaped multi-faceted enabler, I often work in virtual teams with engineers, product, and technical program managers on highly complex and urgent projects. When the V-teams form to tackle these projects, everyone approaches them from a different discipline and understanding of what we may need to do to solve the problems, or even more at the foundation, if they are the right problems with the right impact. Many facets can weigh in on what makes execution difficult with virtual teams, but they mostly stem from a lack of clear problems, or alternatively opportunities, and technical decisions.

When problems are opportunities are unclear, we see the following emergent behaviors;

Conflicting Investments - When problems aren't clear, we'll see engineers possibly not know how to execute conflicting investments. I sometimes refer to this as we're executing on both sides of a strategy bet, when we should be picking one side. As an example, if the problem we're working on isn't clear, I may be optimizing my networking proxy for flexibility, while the security team is optimizing for risk reduction. Sometimes flexibility and security are mutually inclusive, but not always. As a result, we end up in the same situation in design reviews.

Uncertainty - When the problems aren't clear, motivated engineers will continue to show up and drive work/projects, but maintain a high degree of nervousness and lack of confidence, and, as a result, execute pretty slowly. Sluggishness may show up because everyone is working on trying to solve the problem they have in their head, but since they aren't sure it's the right one, they move slowly. Sidenote: Uncertainty will impact our settlers and town planners more than pioneers, who are comfortable with ambiguity.

With these emergent behaviors, we struggle to execute with confidence and high impact. So let's make sure we define good problem statements or opportunities.

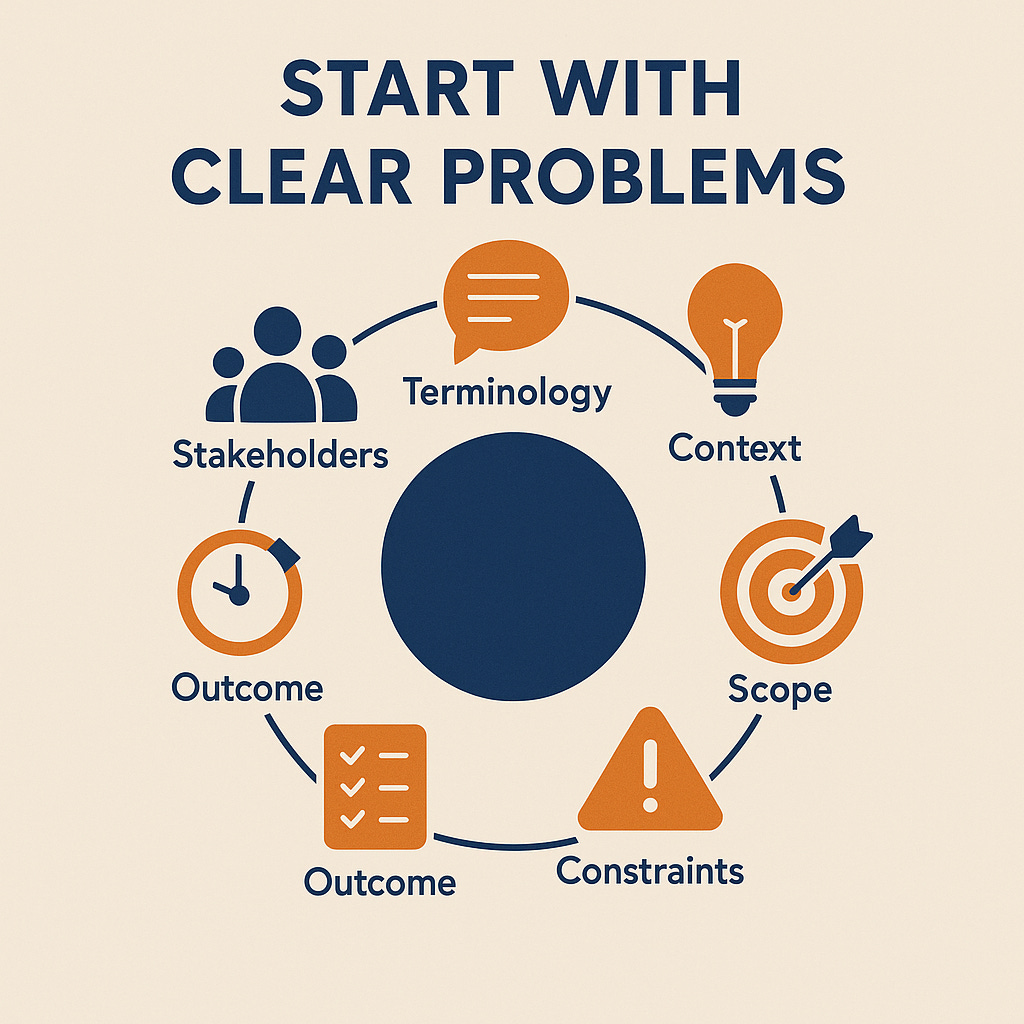

What Does a Good Problem or Opportunity Look Like?

For larger technical projects, I would strongly suggest spending more time than you think on capturing the problem and opportunity. You can use frameworks like SMART to capture a problem statement, but I tend to like to capture it in a narrative format (style preference)

Consider the following elements:

Terminology - You'd be surprised by how often the lack of a glossary has impacted the projects I have led. This is especially true for security engineers when terminology such as risk and threat means completely different things depending on their background.

Clear Context and Motivation - Where possible, this should be data or observation-driven and should help ensure problem solvers understand what is at the root.

Stakeholders - Who are we solving for? Again, this is often overlooked, and we may end up optimizing for secondary stakeholders (e.g., risk, privacy) rather than primary stakeholders (e.g., Product).

Scope - Similar to stakeholders, what do we keep out of scope? I can't stress how much scope has slowed down my projects. Scope can be flexible and time-bound (e.g., our scope in 2025 may look different in 2026 if XYZ occurs). When the scope isn't clear or isn't time-bound, folks may make incorrect investments or debate scope when they could be working on shipping solutions.

Constraints - A flavor of scope, but more tactical. Here we may be setting functional/non-functional requirements. This prevents teams from making optimizations that aren't necessary and also generally creates a lot more focus.

Outcome - When will we consider this problem solved or solved enough? Not all problems or opportunities can be fully realized, so it's important that the outcome is a stretch but also achievable. Open-ended outcomes will often result in lost engineers or scope creep that becomes difficult to manage.

Time - Time is also important, similar to outcome. Without any time boundaries, it becomes difficult to know if we're pacing well or aligned with business needs.

While usually I would cover all of this in a longer format strategy problem statement memo, a short, succinct version of a tiger team working on prompt-injection risk may look something like this:

“Over the next quarter, we will launch a Generative-AI tiger team to mitigate prompt-injection risk. Prompt injection increases credential and data risks, and given recent commoditization of attacks, increases their relevance to our company.

In week 1, we’ll publish a living glossary so “prompt injection,” “guardrail,” “risk,” and “threat” mean the same thing to product, security, and engineering peers. Enabling the product's goals are the primary stakeholders, so risk, privacy, and legal remain vital but secondary to maintain velocity. We will only focus on English-language genAI Chatbot flows slated for Q4; other internal-tool use cases wait for the next planning cycle. Constraints are to mitigate only a subset of prompt injection risks, specifically credential access, while other attack vectors will be revisited later.

We'll measure success by delivering prompt injection guardrails that target 50% of all Chatbots to have egress filtering to prevent credential access, and any leaked credentials are least privileged. Milestones keep us on track: glossary and threat model by day 14; staging prototype by day 45; production rollout with dashboards by day 90.”

Here’s the mapping back to the problem and opportunity framing:

Terminology – Publish glossary by Day 14 covering “prompt injection,” “guardrail,” “risk,” “threat.”

Context – Rise of coimodditized prompt injection attacks.

Stakeholders – Product users primary; risk/privacy/legal secondary.

Scope – English chat flows for GA only, 50% of chatbots.

Constraints – Target credential‑access vectors first

Outcome – 50% of chatbots have egress filtering

Time – 90‑day v-team; prototype by Day 45; prod rollout by Day 90.

While this problem statement is light, it’s salient and creates clarity. Yet, the more we stare at it, we can start to find some questions that, unless we make decisions, may result in the team still lacking clarity:

What level of sophistication of prompt injection should we be able to mitigate?

What if we can’t mitigate the credential risks? Should we consider detections? Is it all or nothing?

Why did we start with credential access and not data access?

I understand I need to bias towards velocity, but what specifically should I trade off to unlock the product while also avoiding too much security or privacy risk?

There are also more questions than will most likely surface when we begin execution. We’ll cover how to answer these questions through technical decision-making in a later post. Let’s kick off this week’s band practice by assessing or creating a problem statement.

This Week’s Band Practice: Problem Statement Clarity Checklist

You can copy this checklist into your next problem doc or strategy you are working on. Gut check this list, if you have 6 or 7 of these ironed out, you’ll probably be in a good spot

Terminology: Are we speaking the same language? Nah, well then create a glossary.

Context: What data proves this is worth solving now?

Stakeholders: Who is impacted first if we fail?

Scope: What’s explicitly out until the next planning cycle?

Constraints: Any budget / risk / flexiblity walls?

Outcome: What metric flips from red to green?

Time: When will we declare “good enough”?

Let me know how practice goes this week and if there is another component of clarity you use that I may have missed!